My Office Neighbor Charles Stevens

(Charles Franklin Stevens, Ph.D.)

By Ruichen Sun

● ● ●

1

In the summer of 2015, Professor Charles Stevens moved into an office next to mine, and we became neighbors at work.

Professor Charles Stevens was 83 years old. Everyone, including me, always called him Chuck.

Chuck liked to wear dark green or navy blue pullovers over plaid shirts, a pair of worn jeans, and black leather shoes. His back was a little hunched. As a result, when he walked, his head was a little forward, as if his brain would like to be ahead of the rest of his body.

At the time when he moved into the office next door, I was going through a rather difficult period of my Ph.D. thesis research. Not too long ago, I had embarked on a new project with a series of new experiments. The amount of data that I collected from these experiments was overwhelmingly large, and I needed help with analyzing them.

When Chuck came to my office for the first time to say hi and asked me what I was doing, I told him about my struggles with data.

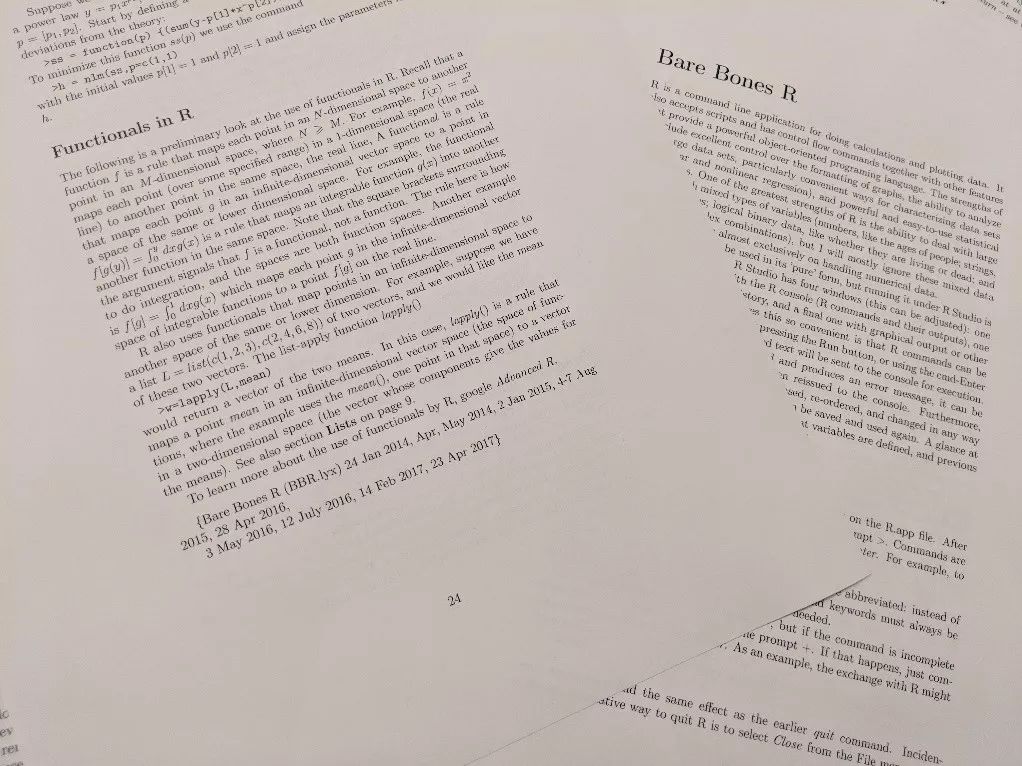

“Do you know R? I am using it these days and I think it can solve your problem.” He said. R was a command-line application for data analysis.

“Oh! I was actually learning to use R.” I was very surprised.

“That’s good! It’s a powerful language. I like it a lot.” He said, and smiled.

“Sure! But… when did you first start using R?” I asked. Chuck was in his 80s, and I was pretty sure that he did not learn programming when he was in school.

“Hmmm, let me think…. Maybe about a year ago? Yeah, sometime in 2014.” He thought for a second and then said, nodding his head.

“Hmm, did you find it hard?” I asked. Learning a programming language in one’s 80s must be hard - or so I thought.

“Well, yes. You know, I am old. So the hardest thing for me is that I forget about the mathematical functions very easily. But I wrote a manual for myself, and I put all the common functions and instructions for use in my manual. Whenever I need a refresher, I read my manual.” He said in a matter-of-fact tone.

“Wow.” I was left in awe.

2

After Chuck told me that he used R for data analysis, I started bugging him with questions often. Most of the time, he solved my questions in a few minutes, and then our conversation digressed onto other random topics.

Chuck liked to share his stories and he found almost everything slightly amusing. Very often he started laughing in the middle of a conversation. When he laughed, both of his eyes squeezed into a line.

Once, he told me that he was the only child of his parents.

“Oh, hey! I did not grow up with siblings either.” I said with a big smile.

“Did you feel lonely growing up?” He asked.

“No. Not at all. Why?” I said. In fact, most of my childhood friends were the only child of their parents. But Chuck was born in 1934, and it must have been very rare to not have siblings at that time.

He shrugged, without saying a word. Chuck seemed to be a little melancholy about this. Later, He told me that during his childhood his family moved a lot. Every move forced him to lose his previous friends, and to find new friends in an unfamiliar new school.

The nomadic life gradually stopped after high school. Chuck went to Harvard University and obtained his B.A. at the age of 21. Towards the end of college, Chuck contemplated becoming a doctor. So after graduating from college, he went on to pursue a medical degree at Yale University.

However, after four years of medical training, he realized that medicine was not what he really wanted.

3

The transition out of medicine did not happen at once.

During his last year in medical school, he was fulfilling his clinical rotation requirements in a hospital affiliated with Yale University.One day he was checking up on an inpatient in the neurology department. His patient stared at him for a few moments and suddenly said: “Doctor, you look very young. You must be better than your peers.”

This comment caught Chuck off-guard.

That night, on his way home, he wondered: Why did the patient say that?

During the final days of his neurology rotation, Chuck thought a lot about that patient’s comment.

Chuck remembered that his college psychology professor used to say: “Everybody says things with two layers of meaning: the first layer is the content, the second layer is intent.”

He asked himself: what was the patient’s intent?

Suddenly, it dawned on him - the patient must be saying: “Doctor, you are so young. I don’t trust you.”

This revelation and its implied pressure of being judged by patients made the 25-year-old Chuck start questioning his career choice. He never really enjoyed dealing with patients or seeing them dying, let alone being judged by them merely because of age.

He had a passion for the brain, but he did not want to become a neurosurgeon (did not like doing surgery on humans)nor a psychiatrist (talking to psychiatric patients can be frustrating). He was leaning towards neurology based on his clinical rotation experience. But that day, that comment from the patient marked the end of his medical pursuit.

Before he finished medical school, he applied to the Ph.D. program at Rockefeller University and got in.

4

Chuck got married before he started medical school. His wife, Jane, was doing her Ph.D. studies in the music department at Yale when Chuck was studying medicine.

When Chuck moved to New York City, his wife moved with him. As she was still a graduate student at Yale, moving to New York City meant that she had to commute for during weekdays. So weekends became the precious for the couple.

Chuck told me about a donut shop in New York.

“There was a lovely donut place in New York close to where I worked. I usually walk to the donut store after work on Friday and buy a big box full of donuts. And on Saturday mornings, my wife and I would be lazy in bed reading the New York Times, enjoying our coffee and donuts. That was my favorite pastime. ” He paused, and then added with a chuckle: “I had no idea that I was giving that up for the rest of my life when my first daughter was born.”

Well, after his first daughter, his second and third daughters came along.

Chuck tried to replicate this Saturday morning tradition several times later. But, the donuts and coffee and Saturdays were never the same again.

One year on Father’s Day, his daughters tried to show their dad their appreciation before he got out of bed. Before heading up to their dad’s bedroom, the girls prepared the coffee, the donuts, and the newspapers with help from their mom. This was by no means an easy task as the three girls had very different ideas about who should bring what to their beloved dad. They were fighting as they walked towards Chuck’s room. By the time the three girls reached Chuck(who was waiting for them, smiling),they became too eager to show off their love that the coffee was spilled on the carpet, and the newspapers were torn apart.

Looking at the mess, Chuck knew that he had forever given up his favorite Saturday morning pastime.

5

Chuck received his Ph.D. in 1964 from Rockefeller University. He took up the assistant professor position at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle and began studying neuron firing activity [1]. His passion for a deeper understanding of the brain and neural function stayed with him, long after he had given up medicine.

To study the properties of neurons and understand how the brain works, one has to study the action potential. When a neuron is not active, its membrane potential is around -70mV. When the neuron is activated, its membrane potential rapidly increases thanks to the opening voltage-gated ion channels on the surface of the neuron. And then action potentials are generated.

For years, researchers, Chuck included, took the neurons out of an animal’s brain, put them in a dish, and measured action potentials from the brain sample.

At the time, voltage clamping was the go-to technique for neuroscientists to study neuronal functions. In voltage clamping, one holds the membrane voltage at a set level, and measures the electrical current changes through the membrane before, during, and after activation [1].

Since the early 1960s, when he started working as an assistant professor at the University of Washington, Chuck had focused on the basic mechanism of neural functions using voltage clamps. His attempt was exemplified in a series of research articles, such as his 1972 paper titled “Inferences about Membrane Properties from Electrical Noise Measurements” and his 1975 paper titled “Voltage dependence of agonist effectiveness at the frog neuromuscular junction: resolution of a paradox” [2,3]. Results in both articles were collected using voltage clamp.

However, there was one major flaw in this method.

6

Voltage clamp measurement targets the entire membrane of a neuron. For a given neuron, there are a lot of ion channels on this neuron’s membrane. All of these ion channels can open and close at any given moment when the neuron is activated.So, gross measurements of electrical current changes of this neuron’s membrane would only yield very noisy results of its activity.

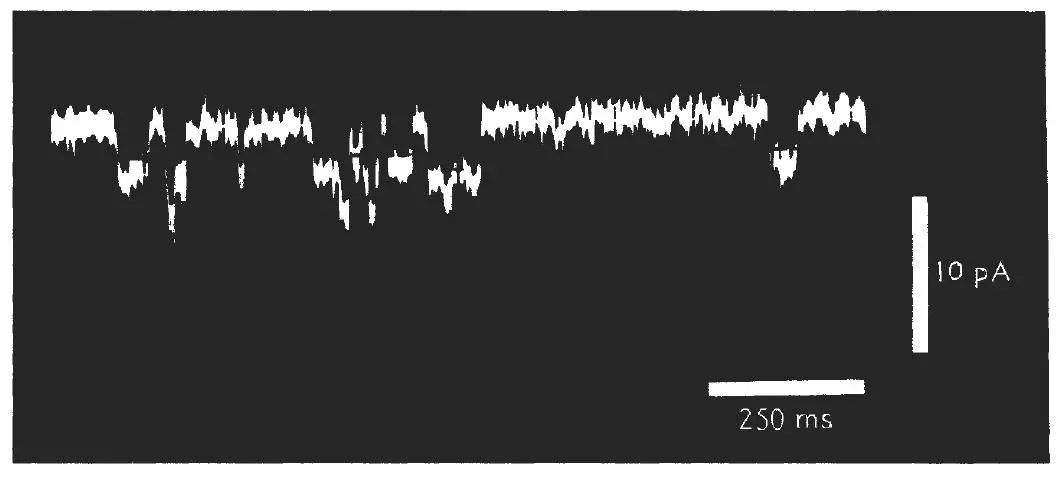

In one of his early papers published, Chuck was interested in the noise between the intervals of two continuous action potentials obtained from the same cell[4]. But his measurements of the action potentials using voltage clamp were always noisy.

With the excess amount of noise, it is hard to tell how the neuron is activated. It was even unsure at the time whether ion channel existed – nobody had ever recorded single ion channel’s activity on a neuronal membrane. Some formulated theories based on the noisy data, but many others were waiting for a definitive experimental proof.

Such dilemma is analogous to looking at the United States’ presidential election results. When one candidate won the election while the other lost, we wouldn’t know how much more votes the winner won without more information. In some states, the winning candidate lost and the losing candidate won. Even for an individual state, not everyone in that state voted for the same candidate. And in the same neuron, not all ion channels open at the same time during activation.

That is the limit of voltage clamp – it tells us whether the whole neuron fires similar to the newspaper headlines of the final election result, while not leaving we wonder which ion channels on the neuronal membrane trigger the firing (or in which states did the candidate win).

7

In the year of 1975. Erwin Neher arrived at Chuck’s lab as a research associate from Germany. Chuck had met Erwin briefly in Germany in1969. The two got along very well: they both were very interested in understanding neuronal activity, especially single ion channel activity. They were taking similar approaches, such as using the same type of neurons (frog neuromuscular junction)and similar glass pipettes for probing the neurons [5-10].

To know that you are indeed measuring from a single ion channel, not multiple ones, you only need one criterion – there should be no noise when you are recording neuron activity. Chuck and many others had been wrestling with this issue for decades: they did noise reduction analysis, noise source analysis, comparing noise from different samples, etc [2, 4, 11]. But reducing noise is not sufficient. The whole neuroscience community needed absolutely no noise.

8

In hindsight, the challenge of achieving this feat was both in hardware and experimental skills. The hardware and equipment, however, were already available in Chuck’s lab at that time. Before coming to Chuck’s lab, Erwin had been trying to measure from single ion channels on neurons in Germany, and these attempts were to no avail [10]. Since Chuck was working on the same topic, Erwin decided to come to Chuck’s lab and work together.

After Erwin arrived, he started running experiments very quickly thanks to the fact that Chuck’s lab was well equipped. Both Erwin and Chuck were doing a lot of such experiments in those days, hoping to perfect their skills and achieve “zero noise” recording. Failures were common. But Chuck always encouraged Erwin to keep trying. Day in and day out, the two discussed the results and brainstormed on how to improve the experiments both from protocols and from equipment aspects.

One day in December of 1975, Erwin started his experiment as usual. He placed the sample in the setup, installed the pipettes on the sample very carefully, and then stared at the oscilloscope. The signals shown on the screen of oscilloscope were as noisy as ever. Erwin moved the pipettes a little, trying his luck.

Suddenly, something happened.

The noisy traces were slowly being replaced by much cleaner straight lines. And then, one spike, two spikes…. More spikes appeared on the screen.

Erwin immediately told Chuck about this and showed him the clean noise-free recording. Erwin said that he was not sure how he got it and that he was very tired at the time of the experiment. But Chuck was excited, and he believed that this was the first-ever single channel recording. He urged Erwin to write up the result in a research paper and publish it while repeating more experiments.

Erwin stayed in the lab during Christmas break doing experiments and writing the manuscript. When he finally finished the draft, Erwin asked Chuck if he should put Chuck’s name on the paper as a co-author.

Chuck thought about it and said: “You don’t have to if you don’t want to.”

9

In life science, it was the standard practice that postdoctoral scholars and research associates colleagues include his or her postdoctoral advisor’s name when publishing research papers. The reasons being that first, they were still considered trainees, and they received advice and guidance from their advisors. Second, they were financially supported by their advisor. In many cases, the advisor applied for research funding, which would be used to pay the trainee’s salary and benefits as well as covering research expenditures. Third, the advisor usually carried out some of the work in the project, such as designing experiments, doing experiments, and writing up the paper.

It was unconventional to not include the advisor’s name.

10

Erwin submitted his manuscript to the Nature journal in January 1976. It was published two months later.

The title of the paper was Single-channel currents recorded from membrane of denervated frog muscle fibres [12]. There were only two authors of the paper: Erwin Neher and Bert Sakmann. Bert was Erwin’s colleague and very good friend in Germany. Bert used to do experiments with Erwin before Erwin moved to the States. But before Erwin came to the States, Bert had not yet figure out how to measure single channel activity [11].

Erwin wrote in the acknowledgment section of the paper: “We thank J.H. Steinbach for help with some experiments. Supported by a USPHS grant fo Dr. C.F. Stevens, and a stipend for Max Planck-Gesellschaft.” [12]

Joe Henry Steinbach was a postdoctoral researcher in Chuck’s lab when Erwin was also working there. The first source of funding, Chuck’s USPHS grant, was used to pay for Erwin’s salary and experiment supplies. At the time, Chuck’s funding was the only source supporting Erwin. The second source of funding was from Max Planck-Gesellschaft, which supported Bert Sakmann.

After that paper was published, Erwin continued to work on single ion channel recordings. In one of his subsequent papers, Erwin wrote: “This work was conducted in the laboratory of Dr. C.F. Stevens at the Physiology Department, Yale University and was supported by N.I.H. grant to C.F. Stevens. We appreciate the help we received through many stimulating discussions with Drs. C.F.Stevens, K.G. Beam, and R.L. Ruff. J.H.S. was supported by a Muscular Dystrophy Association postdoctoral fellowship.” [13] In another one, Erwin wrote:“ Part of this work was conducted in the laboratory of Dr. Ch. F.Stevens, at the Physiology Department of Yale University. E. N. was supported during that time by NS grant No. 12961 to Dr. Stevens…..We want to thank Dr. Stevens for his support and encouragement.”. [14]

Similar to the first Nature paper of Erwin’s, Chuck was not an author of either paper.

11

In 1991, Erwin and his co-author for the paper, Bert Sakmann, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine [15]. Chuck’s name was not on the list.

After all, this office neighbor of mine did not get a Nobel Prize.Or did he?

---End---

About the author:

Ruichen Sun is a Ph.D. student at the University of California, San Diego.

Citations

1. Stevens, C.F. (1969) Voltage clamp analysis of a repetitively firing neuron. In: Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies (H. H. Jasper, A. A. Ward, Jr. and A. Pope, eds), Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, pp. 76-82.

2. Stevens, C. F. (1972) Inferences about membrane properties from electrical noise measurements. Biophys J. 12:1028-1047.

3. Dionne, V. and Stevens, C. F. (1975) Voltage dependence of agonist effectiveness at the frog neuromuscular junction: resolution of a paradox. J Physiol 251:245-270.

4. Calvin, W. H. and Stevens, C. F. (1967) Synaptic noise as a source of variability in the interval between action potentials. Science. 155:842-844.

5. Anderson, C.R. and Stevens, C. F. (1973) Voltage clamp and analysis of acetylcholine produced end-plate current fluctuations at frog neuromuscular junction. J Physiol (Lond) 235:655-691.

6. Colquhoun, D., Dionne, V. E., Steinbach, J. H. and Stevens, C. F. (1975) Conductance of channels opened by acetylcholine-like drugs in the muscle end-plate. Nature253:204-206.

7. Dionne, V. and Stevens, C. F. (1975) Voltage dependence of agonist effectiveness at the frog neuromuscular junction: resolution of a paradox. J Physiol 251:245-270.

8. Neher, E. (1971) Two fast transient current components during voltage clamp on snail neurons. J Gen. Physiol. 58:36-53.

9. Neher, E. (1975) Ionic specificity of the gramicidin channel and the thallous ion.Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 401:540-544.

10. Neher, E. and Sakmann, B. (1975) Voltage-dependence of drug-induced conductance in frog neuromuscular junction. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 72 (6):2140-2144.

11. Calvin, W. H. and Stevens, C. F. (1968)Synaptic noise and other sources of randomness in motorneuron interspike interval. J. Neurophysiol. 31: 574-587.

12. Neher, E. and Sakmann B. (1976) Single-channel currents recorded from membrane of denervated frog muscle fibres. Nature 260: 799-802.

13. Neher, E. and Steinbach J. H. (1978) Local anesthetics transiently block currents through single acetylcholine‐receptorchannels. J Physiol. 277(1): 153-176.

14. Neher, E. Sakmann, B. and Steinbach J. H. (1978) The extracellular patch clamp: A method for resolving currents through individual open channels in biological membranes. Pfltigers Arch. 375:219-228.

15.https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1991/(Accessed April 2, 2018)

制版编辑:黄玉莹 |

本页刊发内容未经书面许可禁止转载及使用

公众号、报刊等转载请联系授权

zizaifenxiang@163.com

欢迎转发至朋友圈

商务合作请联系

business@zhishifenzi.com

▼▼▼点击“阅读原文”,直达知识分子书店!