【国际】在金融科技领域,中国是如何超越美国的?

编者按

bianzhean

尽管美国在技术创新的很多方面都是领先中国,但起码有一个领域是中国领先的。这个领域就是以在线支付和移动支付为代表的金融创新。这一切究竟是如何发生的呢?彼得森国际经济研究所(PIIE)总结了两大原因:1)信用卡的欠缺以及互联网公司的发展刺激了在线支付系统的需求;2)法律保障、监管宽松以及智能手机为在线支付系统的发展提供了动力。

去年中国的一项调查发现,84%的中国人并不担心出门不带钱——这不是因为他们对信用卡或者支票形成了依赖,而是因为他们对自身移动手机的支付手段,比如支付宝或者微信能够被接受很有信心——不管金额多少。中国似乎,至少在这个领域似乎已经超越了美国,因为美国人还在执着于塑料卡片(信用卡、借记卡),以及支票和现金这些东西。中国俨然已经站上了未来金融技术潮头浪尖。这是怎么发生的呢?

关于中国最近金融科技的发展及其对全球商业的影响我们撰写了三部分组成的系列文章,本篇有关中国在线支付崛起的文章是第一篇。

值得注意的是,中国快速发展的第一个要素是中国2000年代早期时支付基础设施的落后,与此同时,互联网公司正好开始扩张。电子商务公司被迫开发自己的支付工具,从而建设成业务遍布全国范围的企业,这是他们的美国同行做不到的。当美国的互联网公司在1990年代开始腾飞时,信用卡已经无所不在并且加入了国际网络。美国的电子商务网站只需要接受信用卡就能处理来自全国任何地方甚至海外的支付,并且具备发起退款的能力(如果订购的商品一直没到货的话可以轻易取消支付),这让买家感到更加安心。退款是信用卡的一项经常被忽视的比较优势(相对于借记卡和银行转账)。

而在2000年代早期的中国,大家基本上还没有听说过信用卡,网上银行也很罕见,借记卡也不能在全国范围使用。实际上,让中国对美国的信用卡开放成为了美国的一项主要的政策目标,这个进程已经被拖了10年,只是最近才得到开放——美国运通设立了一家合资企业。中国体系的原始属性可以在当时在线点对点拍卖网站易趣网的支付过程得到体现:于1999年成立的这家在线公司必须解决一个大麻烦——为其客户所在的每一座城市的每一家主要银行设立独立的账号,因为借记卡只能在同一座城市的同一家发卡银行使用。为了避免跟这套臃肿笨拙的系统打交道,易趣网只好靠送货的接受货到付款。类似Visa和万事达的中国银联到2002年才推出,然后才慢慢地将不同城市和银行之间原先碎片化的系统整合起来。

与此同时,腾讯(中国最大的社交与游戏公司)和阿里巴巴(中国最大的电子商务公司)都建立了自己的支付系统来解决自身业务的特定问题。2002年,腾讯创建了一种虚拟货币——Q币,其客户可以用这种货币来为聊天形象购买游戏物品、数字装备之类的数字产品。其功能类似于礼品卡,这样一来客户跟银行体系完成一次大型的Q币购买之后就能方便地在腾讯系统内用Q币进行网上交易了。

阿里巴巴这种2004年的时候推出了支付宝(现为蚂蚁金服的一部分)用于淘宝的交易。一开始支付宝是作为相互不信任的购买参与者的第三方支付服务的身份出现的。易趣网早在2002年的时候也尝试过第三方支付服务,但这项服务费用太高,所以做不起来。支付宝一开始的免费服务是想将支付推迟到商品到达,这样买家就能在东西一直没到或者是假冒伪劣时信任阿里巴巴可以把钱退给他们了。美国的信用卡退款几乎是一样的功能,所以美国公司就没有太大必要自己去建支付系统来解决这个信任问题了。信用卡的接受度使得第三方支付对eBay和Amazon来说没那么重要。

在线支付系统发展的第二个关键因素是中国政府的支持。中国2004年的电子签名法为在线合同提供了法律确定性,2005年开始《国务院办公厅关于加快电子商务发展的若干意见》等一系列政策表态也为在线支付提供了宽松的政策条件。易趣网的第三方支付之所以失败,部分原因也许是因为它出来得太早了,签名法律还没有到位,而支付宝正好是在法律风险没那么大的时候推出。中国央行等待了好几年,直到2010年才开始通过对该板块的官方监管,并在此后很快发行牌照,这使得市场可以在几乎没有合规性成本、准入门槛以及监管限制的情况下自由发展。相反,美国像Paypal这样的公司却要经历一个逐州进行的、低效的、碎片化的流程来获得货币转移商牌照。

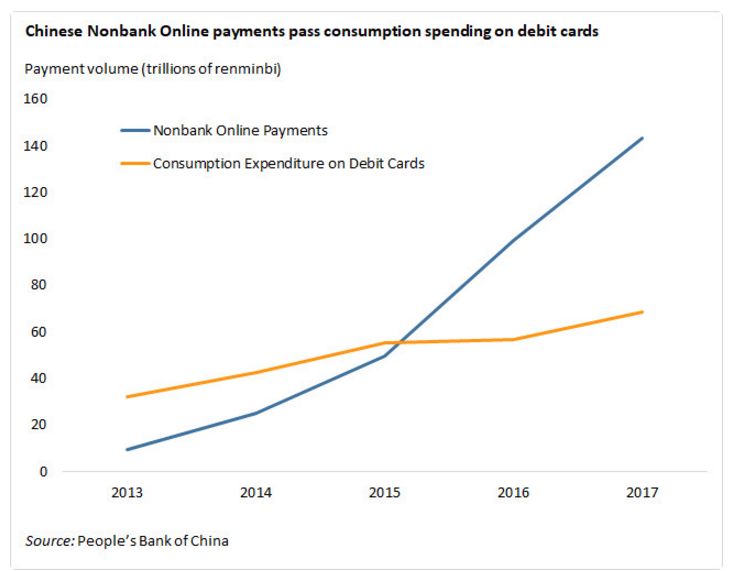

因此,等到监管介入时,像支付宝这样的非银行支付系统已经有将近10年的历史;而到那个时候,由于网络效应以及数亿中国人都用上了智能手机,它们已经达到了临界规模,从而推动在线支付朝着移动支付转移。2013年非银在线支付一下子成为了全球的焦点,当年中国的非银支付处理的交易量达到了9.2万亿元(参见下图)。同样在2013年,支付宝超越了PayPal成为全球最大的在线支付平台。在2013年(第一年提供在线支付量的官方数据)之前对其增长的量化是非常困难的,因为阿里巴巴和腾讯对自己的数据是保密的。2014年非银在线支付几乎增长了170%,并且很快就超过了中国50万亿元左右规模的借记卡消费开支。

黄色:借记卡消费支出;蓝色:非银在线支付

中国在线支付的成功收购互联网公司共生关系的结果,这为他们的支付业务提供了原生的用例。鉴于电子商务占到了中国零售销售的17%,而美国的相应数字是8.9%,所以相对于美国,在线支付更适合于中国的环境。包括小商贩在内的线下业务的采用,比如采用二维码代替NFC或者塑料卡来进行个人支付对此也起到了帮助作用。线下商家使用买家智能手机摄像头来扫描印刷的二维码(或者类似条形码这样的扫描枪来扫描买家智能手机屏幕上的二维码)。这种办法比设立昂贵的联网销售点设备要容易得多,尽管像Square这样的公司已经让美国做这样的事情变得便宜多容易多了。

在在线支付已经根深蒂固之后,腾讯和阿里巴巴的蚂蚁金服还把业务扩展到借贷及资产管理这样的领域。中国的一个关键经验是这些变化不是一夜之间发生的。开发这样的基础设施需要好几年的时间,需要有足够多的消费者信任互联网公司接管其金融生活。但也许最重要的是,金融科技创新之所以出现是因为少数公司无法忍受其环境中有缺失的环节。他们宁愿开发新的、更高效的系统而不愿等待既有者替他们这这件事情给做了。

survey (link is external) in China last year found that 84 percent of Chinese were not concerned about leaving home without any cash—not because they relied on credit cards or checks, but because they were confident that their mobile phone payment methods like Alipay or WeChat would be accepted for any expenses they encountered. China seems, in this area at least, to have leapfrogged the United States, where Americans are wedded to plastic (credit and debit cards), as well as paper checks and cash. China would thus appear to be surfing the financial technology (fintech) wave of the future. How did that happen?

This blog post on the rise of online payments in China is the first in a three-part series covering recent fintech developments in China and their implications for global commerce.

The first factor in China’s rapid progress, ironically, is the backward state of China’s payment infrastructure in the early 2000s, when Internet companies were beginning to expand. Ecommerce firms were forced to develop their own payment tools to build nationwide businesses in ways that their counterparts in the United States were not. When American Internet companies began to take off in the 1990s, credit cards were ubiquitous and joined into international networks. American ecommerce sites simply needed to accept credit cards to handle payments from anywhere in the country and even abroad, and the ability to initiate a chargeback (easily cancelling a payment if goods ordered online never arrived) made buyers feel more secure. The chargeback is an often-ignored advantage of credit cards over debit cards and bank transfers.

In China in the early 2000s, credit cards were virtually unheard of, online banking was rare, and debit cards could not be used nationwide. In fact, it became a major policy objective of the United States to try to open China to American credit cards, a process that has dragged on for well over a decade and has only just now opened (link is external) to a joint venture set up by American Express. An example of the primitive nature of China’s system back then was the payment process for the Chinese person-to-person auction website EachNet: Launched in 1999, the online company had to deal with the hassle (link is external) of opening a separate account with each major bank in each city its customers lived in, because debit cards could only be used in the same city at the same bank that issued the card. To avoid dealing with this clunky system, , EachNet relied on its delivery people to accept cold cash on delivery for many of its online transactions. China UnionPay, a card network analogous to Visa and Mastercard, only launched in 2002 and gradually integrated previously fragmented systems between cities and banks.

Meanwhile, Tencent (China’s largest social and gaming company) and Alibaba (its largest ecommerce company) built their own payment systems to solve specific problems in their businesses. Tencent created a virtual currency called the Q coin (link is external) in 2002 that its customers could use to pay for its digital products like items in games or digital outfits for a chat avatar. It functions like a gift card, allowing customers to make one clunky large payment with the banking system to buy coins and then transact easily online within Tencent’s systems using coins.

Alibaba launched Alipay (now part of Ant Financial) for use on its Taobao online marketplace in 2004 , which started with an escrow service (link is external) for online purchases between parties who didn’t trust each other. EachNet had tried escrow services as early as 2002, but the service was expensive and did not take off.[1] Alipay’s initially free service was designed to hold payments until goods arrived, so buyers can trust Alibaba to give their funds back if the products are shoddy or never arrive. Sellers can trust it to confirm that buyers had put up the funds. A credit card chargeback fulfills virtually the same function in the United States, so American firms had less need to build their own payment systems to solve the trust issue. Credit card acceptance made escrow less important for eBay or Amazon.

The second key factor in the growth of online payments was Chinese government support. China’s 2004 electronic signature law provided legal certainty (link is external) for online contracts, and a series of policy pronouncements (link is external) starting in 2005 called for the “advancement of the online payments system.” It may be that EachNet’s escrow service failed partly because it came too early, before the signature law was in place, while Alipay came at exactly the right moment with far less legal risk. China’s central bank waited years before passing official regulation of the sector in 2010 and issuing licenses soon after, which allowed the market to develop largely free of compliance costs, entry barriers, and regulatory restrictions.[2] In the United States, by contrast, companies like PayPal had to go through an inefficient, fragmented state-by-state process to obtain money transmitter licenses.

Nonbank online payment systems like Alipay were thus almost a decade old when regulations came into play; by that time, they had reached critical mass thanks to network effects and the hundreds of millions of Chinese using smartphones, driving a shift from online to mobile payments. Nonbank online payments were catapulted into the world spotlight in 2013, when providers in China processed RMB 9.2 trillion in transactions (see figure below). Also in 2013, Alipay surpassed PayPal (link is external) to become the world’s largest online payment platform. It is difficult to quantify growth before 2013, the first year for which there are official data on online payments volumes, because Alibaba and Tencent keep tight wraps on their data. Nonbank online payments grew at almost 170 percent in 2014, and soon after exceeded consumption spending on China’s 5 billion or so debit cards.

The success of online payments in China is the result of a symbiotic relationship with Internet firms, which provided the original use case for their payment business. Since ecommerce accounts for 17 percent (link is external) of retail sales in China and only about half that, 8.9 percent (link is external), in the United States, online payments fit into the Chinese environment more than they have in the United States. Adoption for offline businesses, including tiny street vendors, has been helped along by their use of QR codes for in-person payments instead of near-field communications (NFC) or plastic cards. Offline merchants use the buyer’s smartphone camera to scan a printed code (or a scanner like those for bar codes that can scan a QR code on the buyer’s smartphone screen). This method is far easier than setting up an expensive point-of-sale machine connected to a network, though firms like Square have made it cheaper and easier to do so in the United States.

Tencent and Alibaba's Ant Financial expanded into financial services like lending and asset management only after online payments were well entrenched. One key lesson from China’s experience is that these changes do not occur overnight. It took years to develop this infrastructure and for enough consumers to trust Internet companies with aspects of their financial lives. But perhaps most importantly, fintech innovation came about because a few companies would not accept missing pieces of their environment as a given. They built new, more efficient systems rather than waiting for incumbents to do it for them.

译者:郝鹏程

来源:36Kr

行业时事

案例分析

监管动态

深度观察

活动&荐书

清华大学五道口金融学院互联网实验室成立于2012年4月,是中国第一家专注于互联网金融领域研究的科研机构。

专业研究 | 商业模式 • 政策研究 • 行业分析

内容平台 | 未央网 • "互联网金融"微信公众号iefinance

创业教育 | 清华大学中国创业者训练营 • 全球创业领袖项目(报名中!点击查看详情)

网站:未央网 http://www.weiyangx.com

免责声明:转载内容仅供读者参考。如您认为本公众号的内容对您的知识产权造成了侵权,请立即告知,我们将在第一时间核实并处理。

WeMedia(自媒体联盟)成员,其联盟关注人群超千万